give us glorious technicolour / bring back the world fair

Every few years about this time I watch Meet Me in St Louis. I think of it as necessary seasonal soul food for the English midwinter. Meet Me in St Louis is shot in Technicolour which is both a technology - a colour film process that captures and reproduces vivid oversaturated colours - and more importantly an aesthetic. Technicolour's excess, heightened palettes and drama was a narrative shorthand to signal movies that were fantasies and epics and romances. If you've seen Gone with the Wind, you know how Technicolour looks and feels.

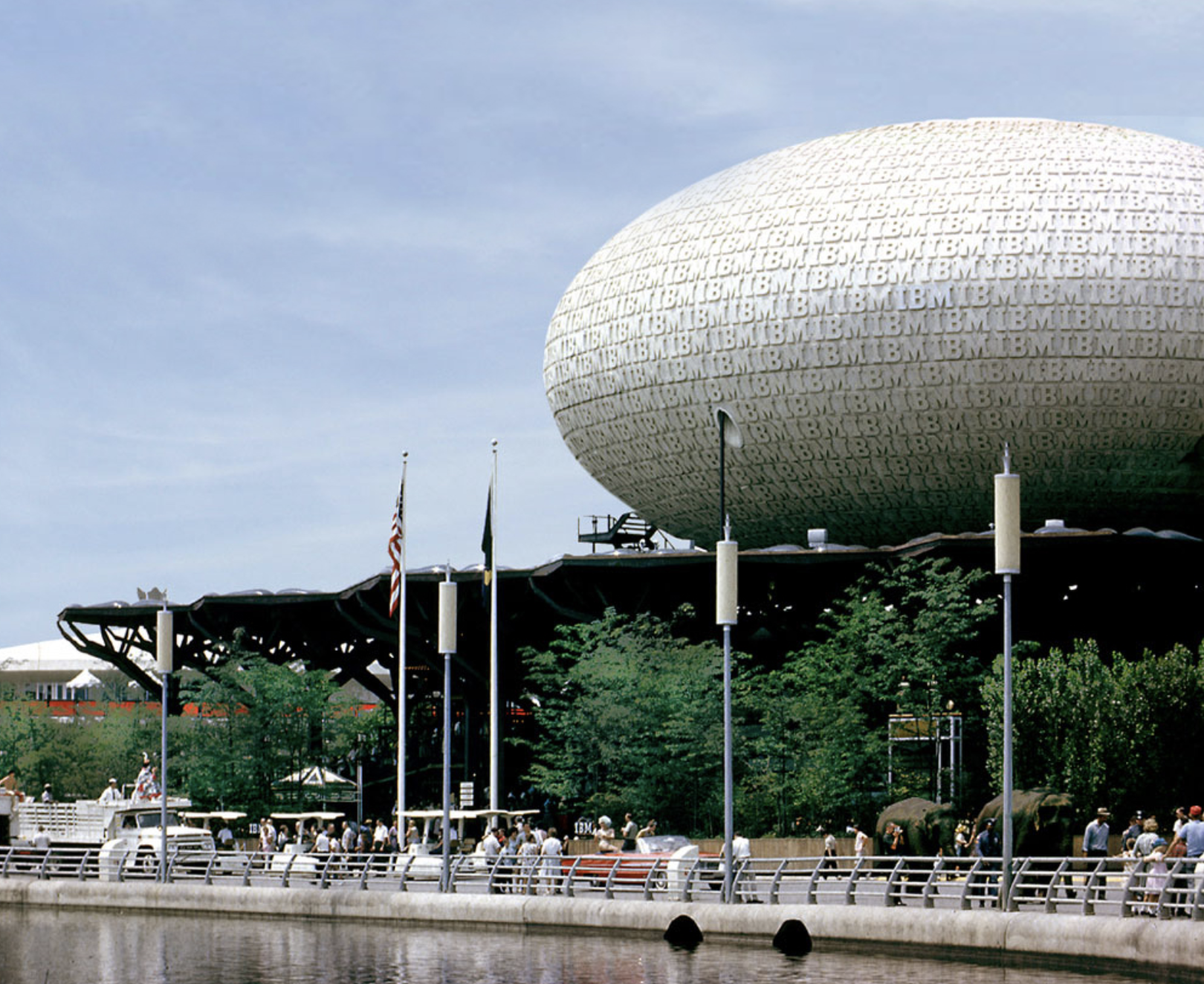

Back to Meet Me in St Louis. It's 1904. Judy Garland's dad has been offered a job in New York (hello, modern migration patterns) and she's fuming because if they move it means she'll miss the upcoming St Louis World Fair. In 1876, Alexander Graham Bell launched the telephone at the Philadelphia World Fair. The Eiffel Tower was chosen from 100 submitted designs as the entrance to Paris's World Fair in 1889. It was meant to be temporary and loved so much it was kept. In 1939, Roosevelt's opening address to the New York World Fair was broadcast across the US to launch broadcast television. After several decades of patents, trials and error, the touchscreen got its first public demonstration at the Knoxville World Fair in 1982. Cherry Coke, the Ford Mustang, Bell Lab's picturephone, the ice cream cone, the Ferris Wheel...all these inventions and technologies first hard launched to the public at a World Fair. What's a World Fair? They're one of those huge cultural phenomenons that seems to have slid out of view. Every few years, for centuries, a particular city or state would stage a giant outdoor and indoor exhibition of the latest marvels. World Fairs promoted the idea, archiac and hippie at it may sound now, of collective progress. The hosts cemented themselves as being at the heart of what was new. This wasn't just the host city or country but also the master builder behind the push; building buy-in, raising money, getting a highly complex physical space with many stakeholders live plus all the surrounding local infrastructure from hotels to roads. Every great book about World Fairs is urban development plus mass market cultural moments. Like Erik Larson's excellent Devil in the White City, set during Chicago's 1893 World Fair, partly about its architect Daniel Burnham who also designed Selfridges in London, NY's Flatiron building and much more, and partly about H.H. Holmes and how the dawn of the roadroad enabled migrant work's flight to cities and America's first serial killer. I spent the break reading Joseph Tirella's Tomorrowland on everyone's favourite urban villain Robert Moses and the 1964-1965 World Fair. This book reads like a Safdie movie (go see Marty Supreme); full of what I imagine to be good New York faces, financial sleight of hands, people outrunning each other, energy, pace and change. You can read what time it was in the wider world through looking at the tone, style and content of a fair; 1964-1965 was one of the first where the number of corporate branded pavilions exceeded the nation state presence. One look at IBM's pavilion, designed by Eero Saarinen and Charles Eames, and you know they were the big tech dog of their day (more photos here).

The only time International Business Machines ever looked chic John F Kennedy activated the countdown clock for this Fair before his assassination. Disney tested out the East Coast market for their first theme park through the multiple experiences they built for Ford, Pepsi and the first mass market anamatronic with their Abraham Lincoln robot. Ken Kesey started his infamous cross country bus road trip to get there. The Beatles played. Malcolm X and CORE protested racist hiring practises. Andy Warhol got an early big break in his commission, screenprinted 13 of America's most wanted men for the side of the New York State pavilion which was seen as distasteful and painted over in just two days. Imagine walking around the future for the price of a dollar (1964 entry price was $1 = $10.64 in today's money). This was absolutely a mass market moment; 51.6 million people went to this 1964 Fair for education, entertainment and enlightenment. That's roughly the population of the UK at the same time.

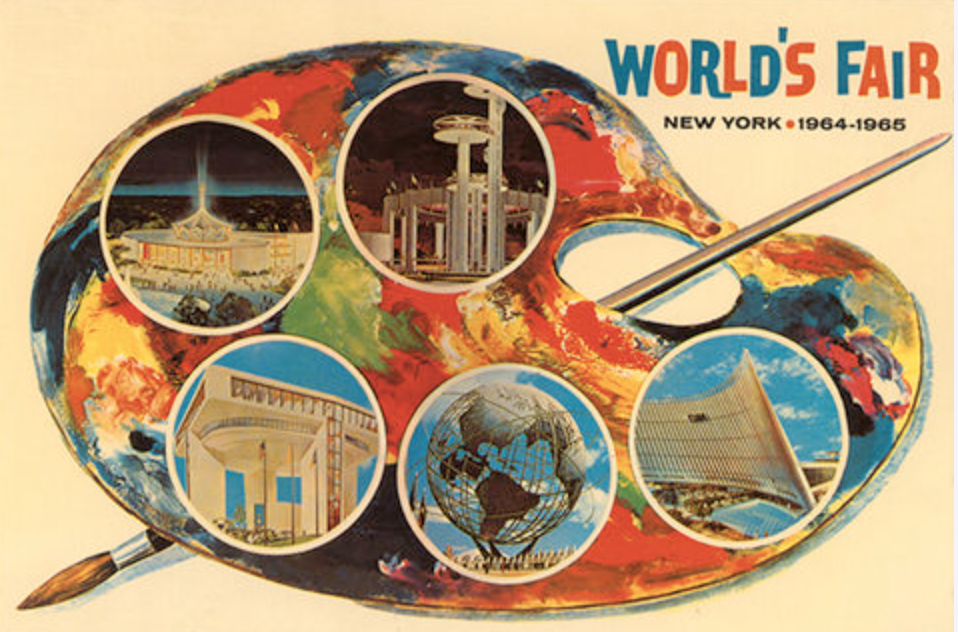

World Fairs were large, diverse spaces - 646 acres in New York across what's now Flushing Meadows in Queens - but, within them, they had what I think of aesthetic coherence. The pavilions and spaces each had their own styles - which you can see on this promotional poster - but one master builder had planned out the overall flow and set the wider theme. Chicago 1893 was nicknamed the White City for its Beaux-Arts vibe. New York 1964 was Tomorrow-land. Aesthetics don't stand alone; they are a consequence and an embodiment of your opinions about the world and how you want it to be. 2025's startup scene is not that different. There's a moral dimension to everything and it matters what we build, invest in and make money on. Most technology IS about collective progress, after all. And Patrick Collison calls it correctly that there's a vibe shift going on that I feel, too. But the sheer perception lag between the proper cutting edge of progress, especially in AI.... the gap between how my very smartest and most engaged friends have developed absolute superpowers and even other friends in tech who haven't or don't want to keep up ... I believe the outputs of all this innovation can be amazing for humans collectively; whether it's doing away with repetitive poorly paid work in the case of physical intelligence in factories -- the missing factor in the "AI takes jobs" debate; there is subjectivity in what makes a "good" or "bad" job everywhere, and there is such a thing as a not-good job we should agree we want to automate -- or moving compute off-planet. But the pace of change means we as technologists have done a poor job of communicating outside our own sector. Yes, Twitter launch videos, podcasts and adverts exist. Yes, early adopters who do not work in technology will always exist. Is that enough? I don't think so. Without effort here, we can't be surprised at waves of push back, anger and fear about technologies being rapidly deployed but not explained. Telling family over the Christmas dinner table about Waymo coming to London is one thing; showing them a video of me loving my self-driving taxi in San Francisco is another; neither is as good as the dazzle of watching an autonomous car safely navigate the complex context of the city right in front of them. You've got to FEEL things, sometimes. I'm not sure the internet's mass distribution gives the same sense. Which is how I came back to the World Fair. A large-scale physical space, at an affordable price point, public/private, designed for a mass market audience of every age and type who are there not just as future consumers but also as citizens. The last Fair held in the west was in 2015 in Milan; the last in the US was in 1984. It shouldn't surprise any readers of my last few newsletters the last World Fair was held in China. Patrick Collison and Tyler Cowen just launched this program seeking to grant make to artists, architects and designers working to define New Aesthetics in 2026 and beyond. I hope they also collate the various work funded and find a way to physically show it to the widest group possible (my first thought reading it was; bring back the world fair). It's the most hackneyed quote possible but still true; The future is already here, just not evenly distributed - William Gibson. Happy New Year, Sarah ✌️

|